Even the most progressive companies face a frantic catch-up with the scale and speed required of the sustainability transition. In the absence of the systemic change that economies need, sustainability professionals and supportive senior leaders should sharpen their case and maximize their impact (see Exhibit 1).

We’re writing to anyone who wants to progress sustainability in this brutal political and business environment.

There are numerous traditional business cases for sustainability across the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) spectrum, including energy and resource efficiency, consumer engagement, employee purpose, and resilient supply chains. But we need so much more—especially from those already ahead.

Sustainability is about survival and people thriving alongside nature.

Source: HFS Research, 2025

The head of sustainability for an international utility recently lamented to us the state of the firm and the industry’s transition plans. They acknowledge that in most future scenarios compatible with sustainability—especially decarbonization or “net zero”—the company would not exist, certainly not in its current form. It has no clear pathway to transition under current shareholder pressure. The technologies to decarbonize exist—but less so the political and economic system.

Oil and gas transition strategies rely on speculative bets and hopes, not viable pathways

The oil and gas industry is both vital for the transition and its biggest blocker. Recently, a senior sector leader described oil and gas transition plans as, essentially, “bets” on technologies that would either replace or allow the industry to continue operating, like nuclear fusion, hydrogen, or carbon capture… and the hope that sufficient capital might exist to buy up renewable energy capacity when needed.

The oil and gas industry has also dropped the pretense of investing in clean energy and a managed transition. Most major firms are rolling back clean energy investments, in contrast to the broader energy system. Renewable energy has just surpassed coal globally to be the largest source for the first half of 2025. The International Energy Agency expects clean energy to receive double the investment in 2025 compared to fossil fuels, at $2.2 trillion vs. $1.1 trillion. However, the oil and gas industry, which is interlinked with every system globally, from finance to consumer products, maintains that it cannot make the necessary transition.

Carbon markets reveal deeper cracks in the systems supposedly providing solutions

Carbon markets are a systems failure. Less than 16% of offsets are effective in reducing emissions. Deep-seated issues include double-counting by buyers and sellers, credits for projects that would have been built anyway (like profitable solar and wind farms), non-permanent projects (such as trees planted then burnt in wildfires), and “leakage” due to projects causing negative side effects or emissions simply moving elsewhere, like logging.

New California regulations will cover 4,000 of the largest companies—one example of the gradual system change happening beneath the negative media and political mood. Widespread studies indicate that disclosure is increasing, not decreasing, and that C-level executives are advancing with intrinsically profitable sustainability initiatives in large companies—the ones that govern how systems operate. The UK is also discussing its new disclosure standards, including the possibility of transition planning, and Singapore has newly released anti-greenwashing guidance.

Even as coalitions like the Net Zero Banking Alliance wind down due to a series of politically motivated withdrawals (most of these financial companies maintain their decarbonization targets nonetheless), there are many examples of cross-industry collaboration.

Recently, we’re seeing firms like DHL (shipping fuel), Levi’s, Mars, and Cargill (all using renewable energy), as well as Saint-Gobain and Schneider Electric (in the cement industry), experimenting with coordinating sustainability through their supply chains. These moves signal that the largest businesses see change coming and want to dictate it.

Voluntary disclosure platforms, such as the Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) and the CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project), continue to increase their participation numbers and are increasingly focusing on transition plans in addition to the disclosure of impact, risk, opportunities, and target setting.

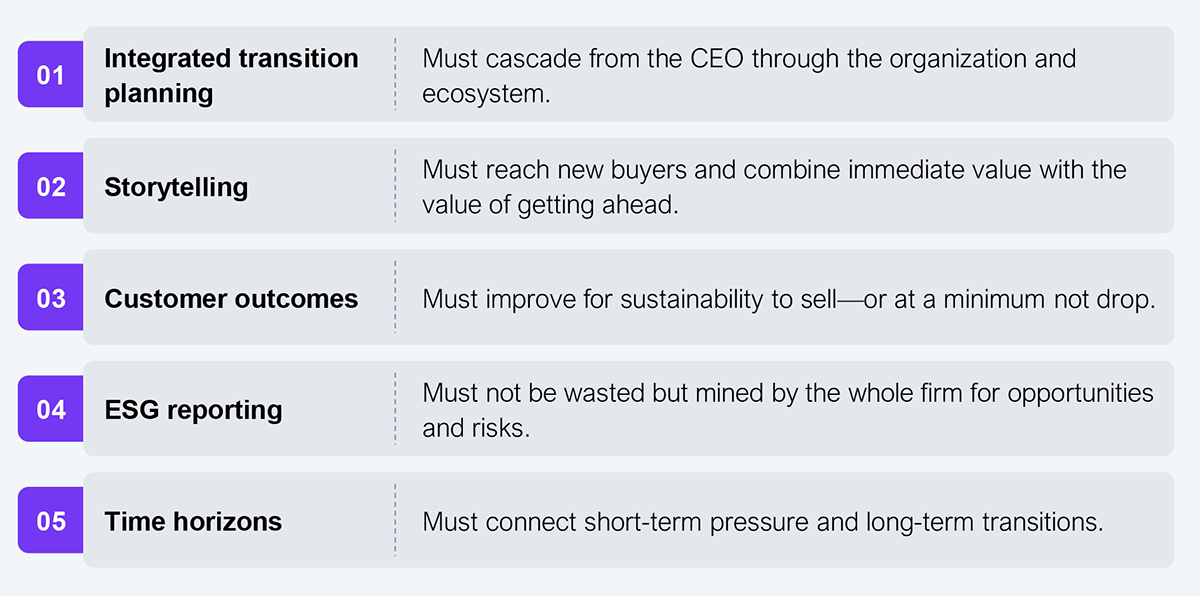

The business case for sustainability will lie in integrated transition planning, extending far beyond the sustainability function, and connecting the CEO, board, CFO, risk managers, consumer teams, supply chains, and further into the entire organization and its broader ecosystem.

Last year, leading up to COP29, we published that we knew we had to solve sustainability through transition planning and critical mass. That still stands. It just needs to be embedded in organizations through clear messaging from the top, incentives, and broken-down interconnected targets.

Sustainability needs to go far beyond the Chief Sustainability Officer. Years ago, at COP26 in Glasgow, we spoke about the wildly different priorities of CEOs and procurement and supply chain leaders on sustainability. Those disconnects remain.

We know where regulation is heading. There is still time to get ahead and lead, as we often communicate.

Sustainability startups, for example, are mixing their messages to tap into AI and innovation budgets—based on the targets of those budgets, for instance, consumer outcomes.

Sustainability won’t sell if the product sucks

Consumers need sustainable products to be at least as good as, if not better than, their traditional, less sustainable alternatives.

Survey sentiment toward paying more for sustainability only holds so far in the real world. Unilever, therefore, through its Persil brand, has created a laundry detergent specifically designed for cold, 15-minute cycles, saving consumers time and reducing energy costs. This could be an all-around win for consumer outcomes—but how to find those outcomes?

Stop filing ESG reports—and start mining them

Don’t waste the value in ESG reporting. It already demands deep analytics and materiality assessments. Use reporting to unlock value—optimize energy, redesign supply chains, and find new revenue sources.

Future-proofing needs cross-horizon thinking

Our final recommendation addresses integrated transition planning. Not only must these plans work throughout organizations and their ecosystems, but they must also work across time horizons, connecting the pressures of the present, the near-to-mid-term future, and the long-term future. For example, consider the financial sector linking day-to-day account managers, three-to-five-year portfolio managers, and long-term risk managers; or the energy sector ensuring its innovation teams work together more closely across time horizons and are aligned with the business strategy.

Sustainability leaders risk losing this decade and so must embed their transition plans across the business.

Sustainability professionals and supportive executives will only take the chance to define the future by refining the moral and financial cases for sustainability in all its forms. Those cases must flow throughout organizations’ day-to-day and their strategic planning.

There will always be more work to do. Sustainability will inherently be tough. Changing systems and the status quo always is.

Keep going.

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get StartedIf you don't have an account, Register here |

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get Started