The latest US logistics figures showed that costs surged to US$2.6 trillion in 2024 (accounting for nearly 9% of GDP), rising faster than what most fleet owners can offset. The driver workforce will head toward a 174,000-person shortfall in 2026, capping productivity at less than 60% and pushing fleet operations past their breaking point.

This labor shortage makes truck autonomy the only scalable path to protecting service levels and controlling cost-per-mile for fleets. With autonomy accelerating faster than enterprise readiness, COOs must invest now to avoid structural disruption.

The labor gap will lead to a structural capacity ceiling on truck fleet operation by 2026. Incremental fixes such as driver incentives, performance monitoring, route optimization, third-party logistics, and fleet-tracking systems aren’t sufficient. In 2021, a shortage of drivers forced FedEx to reroute 60,000 packages in a single day to keep up with service-level agreements, adding US$470 million in costs and leading to a 7% decline in quarterly profit. More than 5,000 large trucks were once involved in a fatal crash, a 43% increase in the past decade and rising, primarily due to driver fatigue, speeding, distractions, driving conditions, and mechanical failures.

COOs can’t buy their way out of the shortage, leaving autonomy as the only lever left to maintain route coverage. Truck manufacturers have been developing multiple levels of autonomous trucks. Daimler Truck is pioneering it. In 2015, it became the first company in the US to test driverless trucks after Nevada granted a license for its Freightliner trucks.

Daimler Truck is one of the world’s largest commercial truck manufacturers by revenue (EUR 54.1 billion in 2024), offering Level 2 autonomy for driver assistance. Its target market is the US for its wide highways, long-haul trucks, and regulatory policies, with plans to introduce Level 4 autonomous trucks by 2027. To succeed, two components are needed: (i) an autonomous truck platform based on the Freigthliner Cascadia, with in-built redundancy for braking, steering, power, and communication, and (ii) the virtual driver itself connected to autonomous specific sensors.

As per the SAE International’s J3016 standard, the levels of autonomy in the automotive industry are as follows:

Angelin Mary, Vice President, Vehicle Computer Platform at Daimler Truck, shared her perspectives on this emerging technology: “We plan to deploy autonomous trucks in a hub-to-hub model. Human-driven trucks will take over last-mile connectivity from the origin to the first hub and the last hub to the destination.”

Daimler’s market entry with internal combustion engine-powered trucks is planned for 2027, building on last year’s launch of the first battery-electric autonomous truck based on the Freightliner eCascadia. This sets up the autonomous platform for a drivetrain-agnostic future, wherein only the drivetrain differs while the electronics are largely similar. The fleet owner would decide the level of autonomy depending on the maturity of talent, infrastructure availability, investment appetite, quality of service and products to be handled, and ROI expectations.

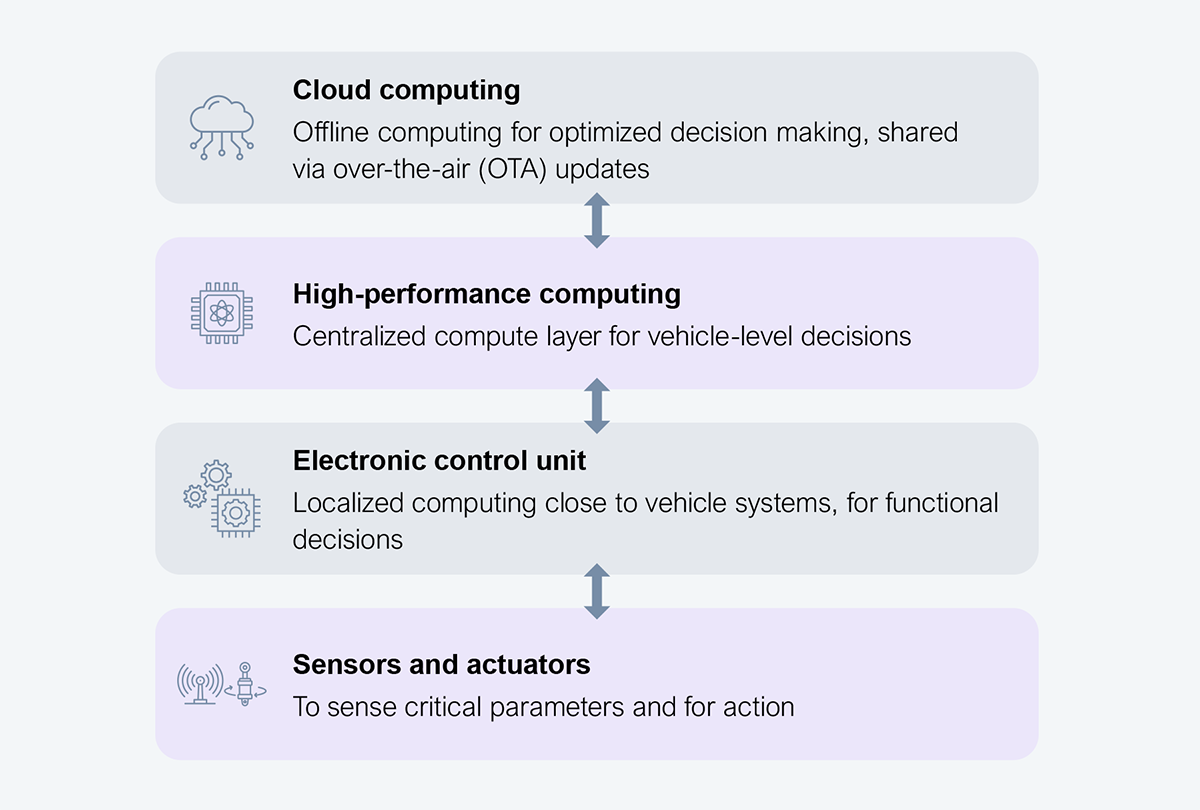

To enable this level of autonomy, the computing architecture is built on a hierarchy of diverse systems, ranging from central cloud computing to onboard high-performance computing, electronic control units (ECUs), sensors, and actuators (see Exhibit 1). Diverse sensors (radar, LiDAR, and computer vision) complement one another with their input fused for safe driving.

Source: Daimler Truck, HFS Research, 2026

When determining which features (and the associated decision making) should reside at a layer, the cost considerations, required capabilities, and latency constraints must be kept in mind. Some critical decisions must also be taken in real time at the edge. Others can be taken offboard in the cloud, enabling ongoing improvements through over-the-air upgrades. The architecture itself is evolving from multiple ECUs for each function to more of a zonal electrical/electronic (E/E) architecture, where a central computer oversees the ECUs, with backup for electronic redundancy.

Truck makers face multiple challenges: scaling up pilots, infrastructure unavailability, high upfront costs, strict local regulations, and the need for public acceptance, making partnerships essential to cover the capabilities they lack. The US Postal Services, in fact, ran a two-week pilot with autonomous trucks for mail delivery between Phoenix and Dallas, with plans to run fleets on 28,000 rural routes by 2025, but not much has been written about that.

The range of activities to achieve autonomous truck driving is too broad for any company to handle alone. A recent MIT study reported a 95% failure rate for AI projects and initiatives, with external partnerships reaching deployment twice as often (67%) as internal efforts.

Daimler Truck aims to address such issues. The company works with its subsidiary Torc Robotics on software development for the virtual driver, enabling parallel work tracks to speed up final delivery. While trucks have long design and development cycles with sequential stage gates in a waterfall model, onboard software for autonomous driving follows agile methodologies with a few week-long sprints.

Another approach is to adopt Volvo’s transport-as-a-service (TaaS) model. This involves making upfront capital investments, offering the truck, its onboard software, and services such as maintenance and repair, all bundled as a solution in an opex mode with usage-based billing. DHL Supply Chain partnered with Volvo to deploy such autonomous trucks for freight operations on key routes in Texas.

To ensure progress beyond pilots, fleet operator COOs must collaborate with truck manufacturers to understand their product roadmaps and roll out their autonomous truck plans in partnership with OEMs. Without such alignment, initiatives risk remaining stuck in pilot purgatory.

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get StartedIf you don't have an account, Register here |

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get Started