Sustainability has always been a battle of responsibility between policy, consumer behavior, and business. Who moves first? Businesses invest heavily in marketing and lobbying to shift environmental and social responsibility onto consumers. Oil giant BP popularized the personal carbon footprint.

Reducing waste and its environmental, human, and economic damage is no different. Often branded as ‘circularity’, these supply chain-centric goals aim to reduce waste in landfills, eliminate modern slavery and child labor, or decarbonize. These efforts, however, far too typically focus on consumers recycling packaging, or at best reusing, upcycling, or buying products branded as green. Businesses should instead focus on the vast volumes of industrial waste generated by manufacturing, mining, medicine, and beyond, into fashion, food, and farming.

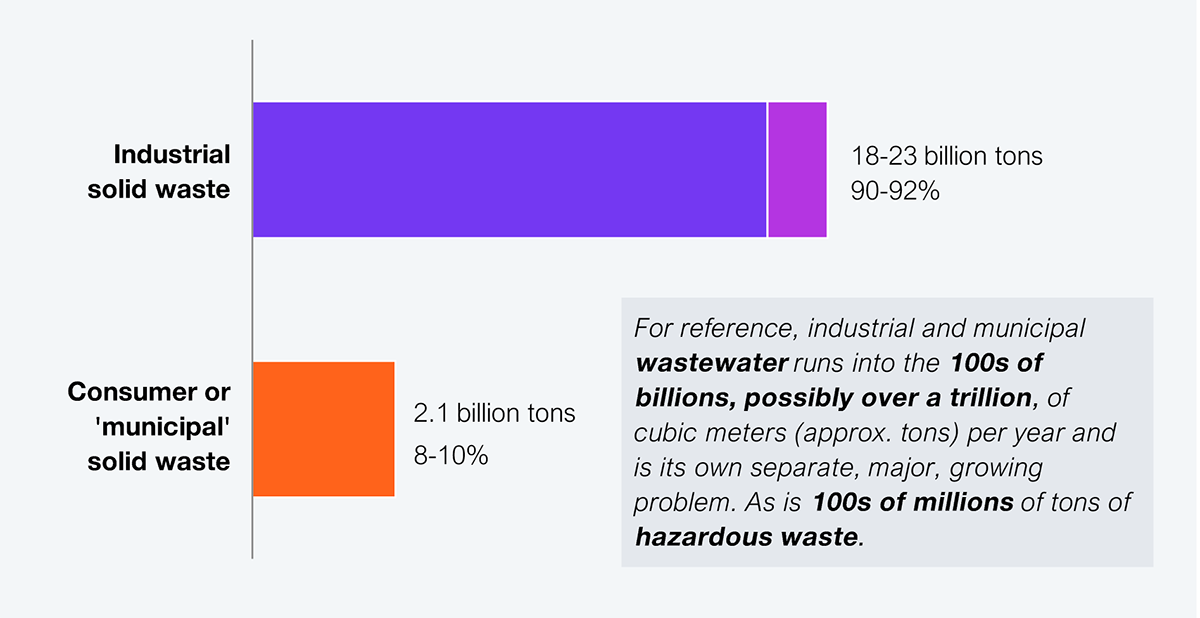

It is difficult to produce definitive numbers on industrial waste. The best estimates suggest, however, that industrial solid waste is an order of magnitude larger than consumer or ‘municipal solid waste’ (see Exhibit 1). Of course, municipal solid waste (including waste from small and city-based businesses) is a byproduct of supply chains that generate waste to provide products or services. But, sustainability needs a wholesale systems change. A critical mass creating tipping points for policy, consumers, and industry. The largest firms dominating how industries and supply chains function must get ahead of that systemic change in a way that works for all stakeholders. They must find the business value in circular economy initiatives such as resilience, efficiency, transparency, and trust, while reducing waste and helping address climate change, nature restoration, water conservation, economic resilience, human health, and so much more.

Source: UNEP, ISWA, World Bank, and broader HFS scouring of the wide-ranging industrial waste estimates out there, 2025

Consumer waste totals 2.1 billion tons annually, according to the International Solid Waste Association (ISWA) and UN Environmental Program (UNEP). Both acknowledge the disparity with industrial waste without providing clear estimates. You can see why.

Inconsistent data, underreporting, and poor definitions of what is included mean waste from sectors such as construction, agriculture, and heavy industry often go unrecorded or misclassified. But we can try.

If we compile global industrial waste estimates, we see many numbers. ‘Business Waste’ suggests 9 billion tons. We see ratios as low as 50:50, with World Bank analysis indicating 20-25 billion tons of solid waste are produced worldwide annually, with about half from industrial sources. That ratio significantly disagrees with the UN analysis of 2.1 billion tons of consumer waste. We also see extreme ratios like 97:3 although that ratio is heavily questioned and likely an overshoot based on old, poorly defined data. In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (although its website mysteriously doesn’t work right now) has reported 7.6 billion tons, suggesting a global volume closer to the World Bank’s 20-25 billion tons, resulting in Exhibit 1’s 91:9 ratio.

For reference, liquid waste from industry and municipalities lies in the 100s, possibly over 1000 billion cubic meters (approx. tons) per year. Hazardous waste is another issue in the 100s of millions of tons. These both deserve separate discussions although the broader theme and urgency of this report holds.

Industrial-scale circularity must break through as feasible and profitable. Although the below are positive examples, they are far from enough or the norm, and some could be argued as greenwashing. These themes must be more broadly embedded in industrial transition plans that meet the global sustainability context.

Coca-Cola is working toward recovering the equivalent of every bottle or can it sells by 2030. 100% of its packaging is already being reported as recyclable. It has invested in rPET (recycled polyethylene terephthalate), aiming for a better brand alignment with conscious consumers and partners.

However, global recycling rates are poor, and regardless of labels, too much (possibly 90%, although, again, estimates are many and variable) of waste is not recycled. And so much waste is processed in heartbreakingly hazardous conditions in landfills.

Tata Steel manages byproducts from its steel production, including turning slag into cement components and utilizing process gases for energy generation. This ‘byproduct valorization’ reduces waste and emissions while generating new revenue streams.

CELSA Group, another steel manufacturer, operates on a near-circular model. In 2022, 97% of its steel production came from recycled scrap using renewable-powered electric arc furnaces. This avoided 10 million tons of CO₂ emissions and reinforced the business case with €6.1 billion in turnover.

Nestlé’s waste heat recovery systems have saved over 1.1 million pounds in CO₂ emissions annually, yielding real cost savings and operational efficiencies. Nestlé is also targeting 100% recyclable or reusable packaging in 2025 and has reduced virgin plastic use by 15%.

Kalundborg Eco-Industrial Park in Denmark is an example of ‘industrial symbiosis’. Companies across sectors share resources and waste streams—for example, using excess heat to warm homes—creating closed-loop efficiencies that benefit businesses, communities, and the environment.

Divert, Inc., operating across US retail, uses anaerobic digestion and RFID tech to transform unsold food into energy. They’ve prevented over 80 million pounds of food from being wasted and secured $1 billion and $175 million in ‘renewable natural gas’ (RNG) infrastructure and offtake agreements with Enbridge and BP.

Supply chain professionals, typically the owners of circularity initiatives, must break down the siloes to the rest of their organizations. We cover the disconnect here. Supply chain teams can integrate the wealth of data, analytics, and baselining that, for instance, ESG and financial reporting generate to find the material opportunities for impact and value in circularity.

While this report aims to be the start of a discussion, not a playbook, broader corporate leadership can begin to move and be a part of the new, sustainable system by: empowering their supply chain teams; making cross-organizational collaborations happen; investing in strategic technology partnerships; invest and partner in their ecosystems to scale proven models like industrial symbiosis and resource-sharing networks; and finally embed circularity and sustainability into core business strategies.

Consumer circularity efforts won’t solve this monumental industrial problem. Consumer-only efforts will also miss the clear positive business outcomes throughout circular processes and value chains.

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get StartedIf you don't have an account, Register here |

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get Started