Public sector procurement should be a driving force for the transition toward sustainability. But that opportunity is going begging. Public sector procurement must build transition plans and collaborate across its vast ecosystem to implement them.

In the absence of transition planning regulation, we have called for organizations to prove the interconnected benefits—environmental, social, and economic—of transition plans. The public sector, as well as any business, can meet that call.

Public procurement has a chance to build the critical mass that generates positive tipping points—pulling policy, consumer behavior, and business toward the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The public sector will also realize a wide range of its own benefits.

In addition to better relationships between business, policymakers, and financial institutions—who can invest, regulate, and insure with more confidence—transition planning can insulate organizations from short-term market and geopolitical turbulence. It can help find material spheres of influence and impact, uncovering opportunities for efficiency, waste reduction, employee wellbeing, supply chain resilience, and broader business benefits proven through sustainability.

We recently attended a Westminster Insight conference on the future of UK public sector procurement. The discussion centered on the UK Procurement Act 2023—aimed at overhauling public procurement regulations, consolidating and replacing previous EU-based frameworks with what is intended to be a more agile and principles-driven system. But the consensus in the room from both the supply, buy, and central procurement functions of the public sector is that the act falls short of establishing an ambitious transition plan for addressing sustainability and benefitting the environment, people, and economy.

The act introduces core principles, such as transparency, value for money, equal treatment, and integrity, while seeking to simplify procurement processes across central government, local authorities, and other public sector bodies. It empowers contracting authorities to consider wider social, economic, and environmental outcomes and to exclude suppliers on grounds of poor past performance, avoiding lock-in to large suppliers regardless of their delivery.

The National Procurement Policy Statement (NPPS) 2025 hopes to complement the 2023 Act by mandating that contracting authorities align procurement with national priorities, embedding long-term policy outcomes into day-to-day commercial decisions.

However, there’s a while to go before the whole procurement function is aligned. Even then, questions remain if the long-term direction is clear enough to support the transition plan required to meet the UK’s commitment to sustainability, including a legally binding net-zero by 2050 commitment. It certainly doesn’t meet the level of ambition the UK should have. It’s certainly not enough to have the systemic influence beyond supply chains throughout industries. A critical mass of transition plans is growing globally from the likes of Ikea, Patagonia, Unilever, ITV, TalkTalk, BHP, and Ball Corporation, as well as Australia, New Zealand, and Brazil regulations based on ISSB standards. But much more is needed.

Public sector procurement has huge potential to drive service improvements and local growth. Public agencies must step up and support the SME ecosystem to compete against incumbents. Encouraging the development of local consortia, for example, grants SMEs greater resilience and potential to scale, derisking investments for the public purse.

— Sam Markey, Taskforce Chair – Procurement Innovation, World Economic Forum

For large suppliers, the emphasis on transparency and performance history will introduce a level of accountability and open doors to those aligned with priorities such as sustainability and social value. SMEs should find a more level playing field, with simplified processes and more opportunities for direct engagement. At the same time, they need to actively build capabilities around compliance, ESG metrics, and partnership models to remain competitive in a more strategically demanding environment.

How we spend taxpayers’ money is the biggest lever the public sector can pull to create change. Curated supply chains, localized suppliers, and dedicated outcomes tracking social and environmental value will design economies rooted in the values of sustainable development.

— Cllr Steve Mason, North Yorkshire Council

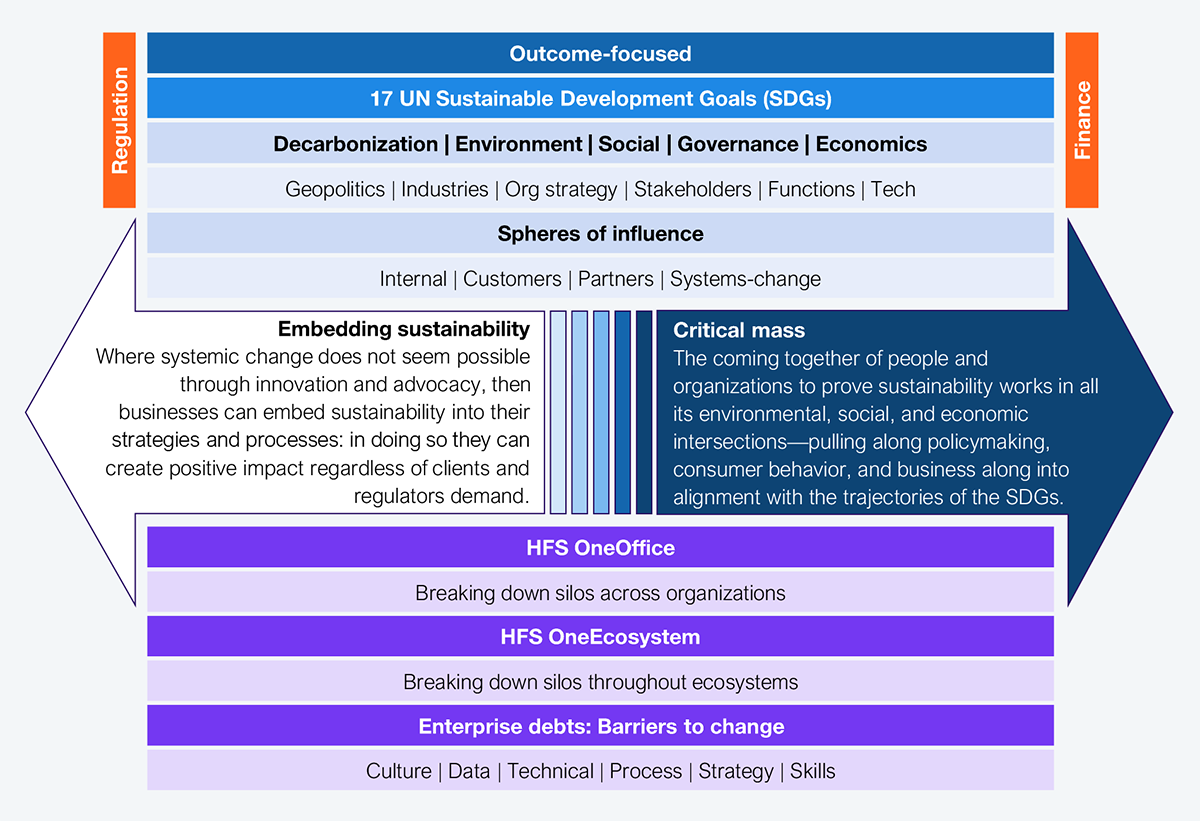

The HFS sustainability framework (see Exhibit 1) is one of the many examples that can outline a template for public procurement to structure transition plans. Starting with a clear outcome focus, those trajectories can be broken down and aligned with international, national, local, and industry dynamics. The most material spheres of influence can be identified (a materiality assessment). Public procurement still has time to get ahead and lead.

The global and national contexts must translate into procurement metrics that align with positive outcomes for people’s lives and local areas. Metrics such as carbon reduction, ethical supply chains, and biodiversity must connect to broader goals such as energy and water affordability, healthy spaces, pollution reduction, and inclusive employment practices. Digital transformation, for instance, must retain a clear focus on outcomes for people, not just technology for its own sake.

Source: HFS Research, 2025

Public sector teams must improve their communication. Procurement leaders at the Westminster conference pointed out that teams buying the same product or service often don’t collaborate, let alone across departments. Even our work leading up to the COP26 UN Summit back in 2021 showed the glaring gap between organizational strategy and the priorities of procurement teams.

That same collaboration must be improved throughout ecosystems of government, customers, suppliers, and society nationally and internationally. Governments must have a clear eye on legacy ‘debts’—barriers to technology and sustainable change that layer on top of each other over time—to best plan and act on the transition.

Public sector procurement must evolve into a proactive force for systemic change to maximize its positive impact. This means embedding sustainable outcomes—reduced inequality, climate action, and decent work—into every stage of the commercial lifecycle. The long term must break down and align with the short term.

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get StartedIf you don't have an account, Register here |

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get Started