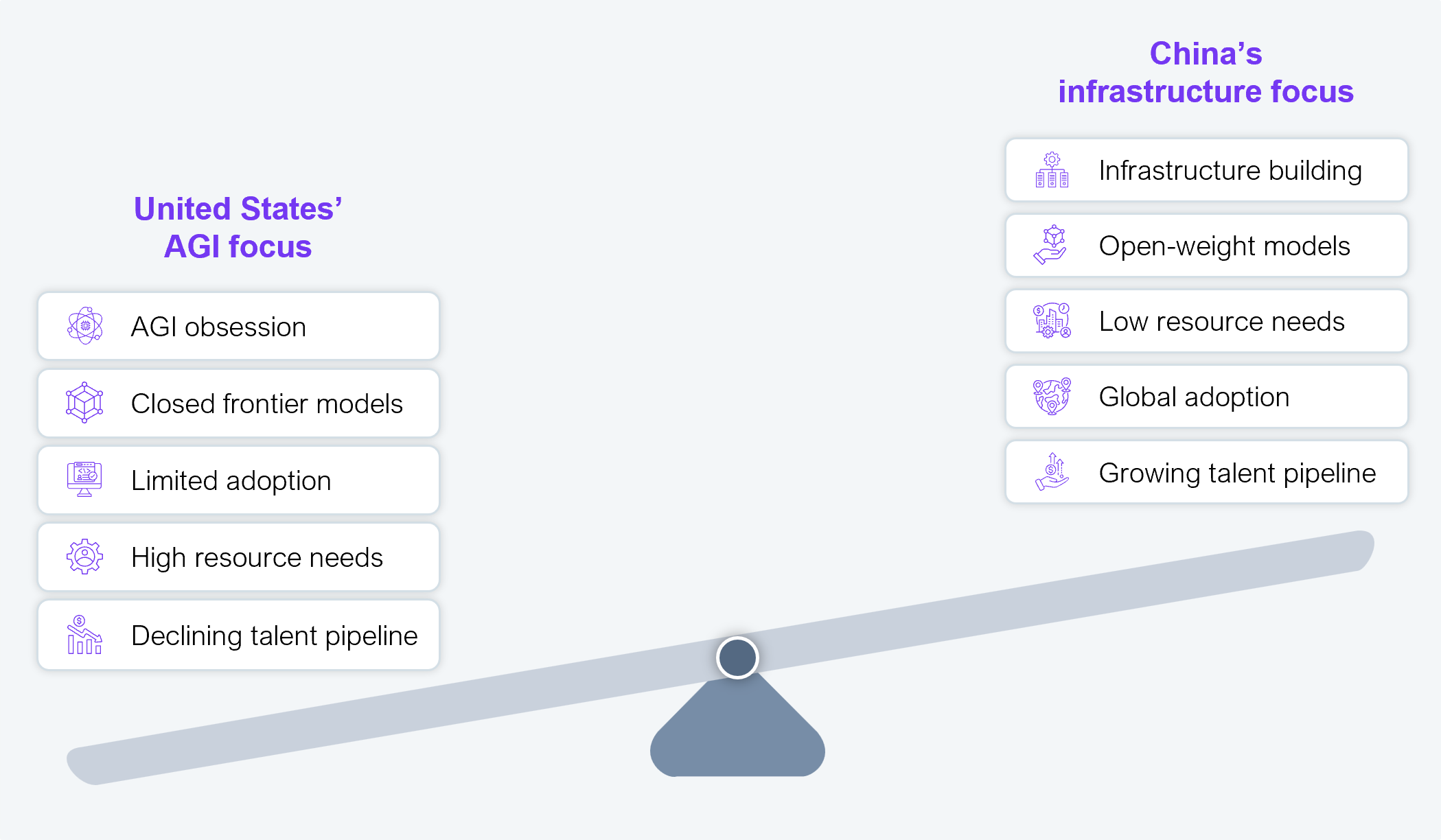

The US is betting tens of billions on artificial general intelligence (AGI), the theoretical breakthrough where AI matches or exceeds human cognitive ability across all domains, through closed frontier models (the most advanced, cutting-edge AI systems like GPT-4, Claude, and Gemini) from OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google.

Meanwhile, China is building something more practical: open-weight AI infrastructure that developers can actually deploy without hyperscale data centers or recurring API fees to US companies. Open-weight AI infrastructure refers to AI models where the trained parameters that make the model work are publicly released so anyone can download, run, modify, and deploy them, as opposed to closed models accessible only through paid APIs.

It’s two incompatible strategies where the country that builds the infrastructure layer billions of people use wins, regardless of who achieves AGI first. American policymakers treating this as a sprint to technological supremacy are losing the systems competition that determines whose AI becomes the default operating layer for the next 50 years.

The current state of play is in Exhibit 1, with AI advantage clearly favoring the Chinese strategy across several critical factors.

Source: HFS Research, 2026

OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google DeepMind are absorbing massive capital to pursue AGI through these closed, proprietary frontier models. The logic is familiar: concentrate elite talent, scale compute aggressively, and assume technological supremacy, which reshapes global power dynamics. This approach is not irrational, folks; it is just narrow.

China, on the other hand, is laying the foundation for global AI adoption. Open-weight models like DeepSeek, Alibaba’s Qwen, and Moonshot’s Kimi are strategic infrastructure designed to be adaptable, localizable, energy-efficient, and deployable on modest hardware. A developer in Lagos, Jakarta, or São Paulo is not paying recurring API fees to US hyperscalers. They’re deploying free Chinese open-weight models, running them locally, tuning them for regional languages, and embedding them directly into workflows. This is not “catching up”; this is platform strategy.

The closest analogy is Android versus Apple at a civilizational scale, where the US dominates premium closed ecosystems, and China is building the default operating layer for most of the world. History is clear. The country that controls the base layer wins, regardless of who ships the most advanced prototype.

Enterprises need to recognize this shift and treat AI as operating infrastructure, not a toolset. That means investing in multi-model environments and agentic workflows, not betting everything on a single platform provider whose commercial model depends on API lock-in and usage fees that scale with deployment.

American policymakers assumed restricting advanced semiconductors would slow Chinese AI progress. In practice, it did the opposite. Denied unlimited compute, Chinese AI labs were forced to architect for efficiency. Sparse activation (activating only necessary model components), memory optimization, lower-precision training (less detailed numbers to represent the model’s calculations), and model architectures that scale down gracefully were survival strategies. DeepSeek’s efficiency breakthroughs happened because of export controls, not despite them.

Most of the world does not have unlimited energy, hyperscale data centers, or unrestricted access to Nvidia’s latest chips. Models designed to work with limited resources can be deployed far more broadly in emerging markets without hyperscale infrastructure, in industries running local operations, and in countries building sovereign AI capabilities independent of US providers.

What was meant to be a bottleneck has become a feature, and China has accelerated domestic chip substitution through Huawei’s Ascend roadmap while Chinese data centers are increasingly mandated to use domestic silicon. The gap is closing not because China matched US chip leadership, but because it designed systems that do not require it. American chip supremacy was supposed to provide an insurmountable advantage, but it’s now becoming strategically brittle.

For technologists and developers, this shift means specialization matters more than ever. Generic cognition is being commoditized by models that run efficiently on modest hardware. The differentiator is building systems that work under constraint, understanding model limits deeply enough to architect around them, and using AI to remove drudgery while preserving the critical thinking that creates durable value.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s Critical Technology Tracker shows China leading in 66 of 74 critical technologies, including advanced materials, hypersonics, energy systems, manufacturing automation, and drones. The US leads clearly in one domain: frontier AI models, concentrating its bets on this single breakthrough domain, while China has built a compounding advantage across the full technology stack.

Robotics, industrial automation, autonomous systems, and defense platforms all require tight integration between software, hardware, and manufacturing. China is the factory of the world and is rapidly absorbing AI into physical systems. The US spent three decades offshoring manufacturing and is now trying to relearn hardware at speed. History favors the hardware leader that integrates software, not the software leader that rediscovers hardware. Manufacturing scale always compounds, while software advantages decay.

China, the Gulf states, and much of Asia are deploying AI faster and more aggressively than the US or Europe. Chinese consumers integrate AI into daily life; their enterprises embed it into operations, and their universities treat AI literacy as a baseline education. This is not just about privacy norms or state direction. It’s about feedback loops, where the more people that use AI in real-world situations, the better companies get at building AI that actually works, which leads to even more adoption, which leads to even better AI. It’s a self-reinforcing cycle. China already demonstrated this dynamic in fintech, e-commerce, and logistics, where real-world deployment raced far ahead of Western peers.

The same pattern is now visible in AI applications. While US companies debate ethics frameworks and European regulators draft restrictive legislation, Chinese firms are shipping, learning, and iterating at scale. For general-purpose technologies, first-mover advantage in application beats first-mover advantage in research. Infrastructure adoption creates lock-in, which shapes standards that determine power. Whoever sets the default way of doing things controls the market, regardless of who has the “best” technology.

Many top AI researchers still work in the US, but the pipeline is changing. US immigration restrictions, politicized campuses, and declining public research funding are making American universities less attractive to the next generation. Chinese universities have scaled AI education dramatically, and leading labs are staffed almost entirely by domestically trained researchers. Twenty years ago, the smartest students in Shanghai or Beijing went to MIT or Stanford. Today, many stay home, receive elite compensation, work on frontier problems, and avoid visa risks and political hostility.

This is not a sudden brain drain, but a slow structural shift. By the mid-2030s, when today’s US-based AI leaders age out, the US will face a replenishment problem it cannot solve with capital alone. China will not. For individuals and enterprises operating in this environment, the strategic imperative is to develop what matters when models commoditize: judgment about when to delegate versus when to think, orchestration skills that coordinate multi-model workflows, and the context and synthesis capabilities that AI cannot replicate. The winners in the next decade will not be those who prompt models most cleverly, but those who redesign roles around accountability and decision making that sits above the AI layer.

When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, in 1957, the US responded with systemic investment in ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency), massive STEM funding, and long-horizon research that seeded Silicon Valley. Today’s response is the opposite, with federal research budgets under pressure, immigration tightening, and education reform stalled. Diversity programs that broaden the talent base are being dismantled. Meanwhile, policymakers assume private capital chasing AGI will somehow substitute for a national strategy.

Venture capital does not build educational infrastructure, fund 20-year research programs, or create societal alignment. China, meanwhile, is running a whole-of-system strategy where education, capital, regulation, and industrial policy are aligned around long-term competitiveness.

The US is running a high-stakes venture sprint and calling it strategy. That is not competition, but abdication disguised as innovation. For policymakers, the path forward requires supporting open-weight models to preserve innovation pipelines and prevent platform lock-in, focusing regulation on deployment and usage rather than knowledge suppression that drives research offshore, and recognizing that compute access and energy infrastructure are national competitiveness issues that require the same strategic thinking applied to semiconductors and critical minerals. The alternative is watching Chinese AI infrastructure become the default global layer while American models remain expensive luxury products accessible primarily to wealthy markets.

China is not trying to beat the US to AGI. China is building the infrastructure layer that, whenever AGI arrives, will make it irrelevant to most of the world if it remains locked behind American APIs, energy costs, and capital intensity. The real measures of victory are whose models power billions of applications, whose efficiency standards become defaults, whose talent pipelines renew themselves, and whose hardware-software integration enables embodied AI at scale. On those dimensions, China is ahead or closing faster than the US, and its advantages are compounding.

American tech leaders celebrating capital raises are winning tactical battles, while Chinese policymakers are playing the strategic game. They understand something the Soviets never did: you do not need to out-innovate America directly. You just need to build the systems that make American innovation optional. Unless the US shifts from an AGI obsession to systematic technological competitiveness across education, manufacturing, research infrastructure, and talent development, the outcome is not undecided but simply delayed.

The cost of inaction is not falling behind in a race but becoming irrelevant to the infrastructure layer that will shape global AI adoption over the next 50 years. AI progress in 2026 is less about achieving AGI and more about scaling deployment, orchestration, and economic accessibility. The winners will not be those with the smartest models, but those who redesign systems, incentives, and infrastructure around them.

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get StartedIf you don't have an account, Register here |

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get Started