The smartphone industry is at a crossroads. Consumers are holding onto devices longer and stretching replacement cycles. Upgrades feel iterative at best and indistinguishable at worst. Flagship pricing is pushing the boundaries of affordability, while tariffs and geopolitics necessitate a review of supply chains. The result is a business model facing pressure on all fronts: cost, demand, and differentiation. For smartphone original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), this is more than a cyclical dip. It is a hard reset demanding a fundamental relook at the changes in strategy, product, and market focus.

The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the vulnerabilities in smartphone manufacturing, and the case for supply chain diversification has only grown stronger. Trade wars, tariffs, and mounting geopolitical risk now demand that OEMs go beyond China+1 and start building diversified and flexible supply chains.

We had previously highlighted Apple’s moves to diversify its sourcing strategy by increasing its footprint in India. The company has ambitions to export India-assembled iPhones to the US market. This move reduces concentration risk (with most iPhones still made in China) and exposure to unpredictable tariff regimes. Samsung, for whom Vietnam is a major hub for smartphone manufacturing, is also expanding operations in India to de-risk its global production model.

The lesson for smartphone OEMs is clear: supply chain agility is now a core competitive advantage. Concentration risk—whether in assembly, components, or logistics—must be addressed before it becomes a revenue event.

Diversification isn’t just about location. It means:

OEMs that shift production quickly, source components flexibly, and absorb policy shocks will protect margins and delivery timelines. Those who wait will find themselves stuck reacting to the next disruption.

Stretched replacement cycles, economic uncertainty, and tariff-driven uncertainty push consumers to delay or trade down their smartphone purchases. Refurbished smartphones are no longer a budget workaround in this environment; they are a core growth lever.

OEMs such as Apple and Samsung already operate certified trade-in and refurbishment programs, but they still have significant room for growth. Done right, refurbished devices enable OEMs to:

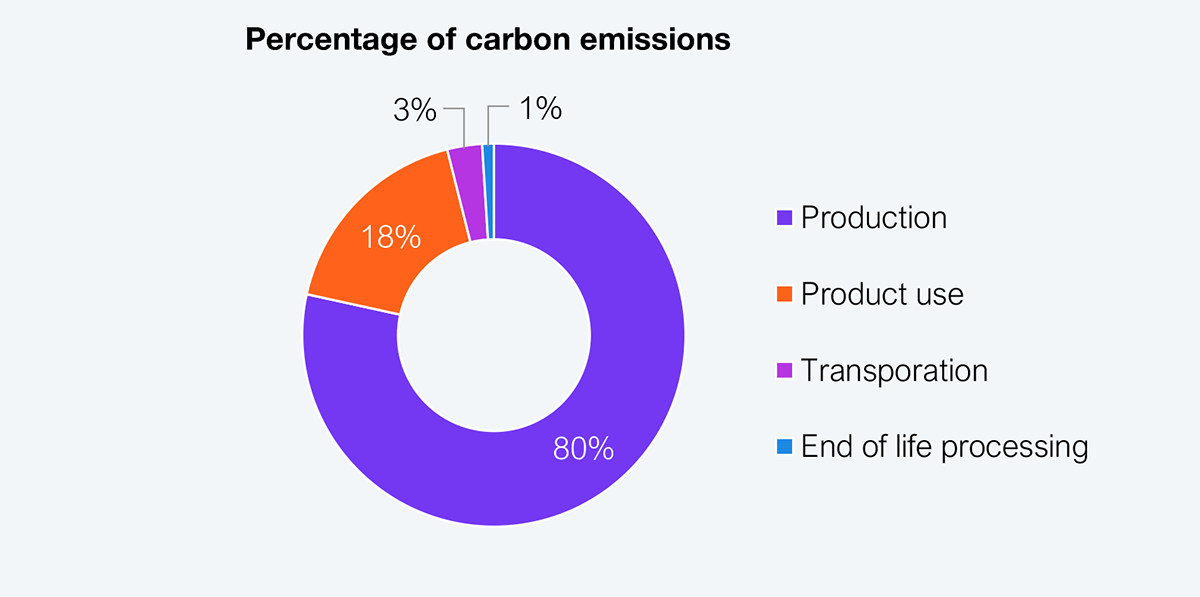

With manufacturing accounting for around 80% of a smartphone’s lifetime carbon emissions (see Exhibit 1), extending the life of existing devices is one of the most impactful environmental, social, and governance (ESG) actions OEMs can take. In an iPhone 16, manufacturing accounts for 80% of emissions, whereas it may be more for older models and smartphones from other OEMs. Refurbishment aligns with regulatory momentum around right-to-repair, e-waste, and circular economy goals, particularly in Europe and North America.

Note: Figures don’t total to 100% due to rounding; the estimates are for an iPhone 16

Source: Apple product environmental report

Refurbishment is also a gateway to emerging markets, where premium demand exists but affordability remains a constraint. For example, one in five smartphones sold in India in 2024 was refurbished. Globally, refurbished smartphone shipments grew by 5%, outpacing the 3% growth in new smartphones, albeit from a smaller base.

OEMs must stop treating refurbished sales as an afterthought. It’s time to invest in the full resale lifecycle—from trade-in incentives and diagnostic automation to resale channels and warranty support. Refurbishment is no longer optional; it’s strategic.

As demand softens in premium markets such as North America and Europe, the next wave of smartphone growth lies in emerging economies. Markets such as India, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Brazil are seeing rapid digital adoption, but price sensitivity remains high.

These markets are no longer peripheral. India has overtaken the US in total smartphone volumes, and other regions across Africa and Latin America are becoming increasingly competitive. The momentum is already visible: fast-moving brands such as Xiaomi, OnePlus, and Transsion are scaling rapidly by offering mid-range and entry-level smartphones that combine solid specs, strong battery life, and local market fit, without chasing the premium refresh cycle.

In many cases, these brands have become the default choice in secondary cities and rural areas, not just because of price but also because of their broad distribution reach and financing flexibility.

To compete effectively, established OEMs must rethink their approach. Growth in these markets requires more than trimming specs or rebranding last year’s models. It demands:

AI is being positioned as the next wave of smartphone innovation, from generative photo editing to personalized assistants. But these upgrades still live inside apps, behind taps and swipes. They enhance features; they don’t change the user experience.

The smartphone interface hasn’t fundamentally changed in over a decade. App grids, notification stacks, and manual navigation still dominate. If AI is to drive real upgrade demand, it must replace this aging model, not just augment it.

OEMs should focus on turning AI into action-first design:

This isn’t about AI as a feature; it’s AI as the interface. That means rethinking UX from the ground up: fewer taps, more prompts; fewer apps, more actions.

Smartphone OEMs don’t need to build their foundation models. Instead, they can integrate deeply with models such as Gemini, OpenAI, Grok, Perplexity, etc. The differentiation will come from how well they embed intelligence across the system, not how many AI filters they add to a camera app.

The smartphone business model is under pressure from all sides: rising costs, slower demand, geopolitical instability, and user fatigue with incremental innovation. To navigate this new normal, smartphone OEMs must rethink where and how they compete:

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get StartedIf you don't have an account, Register here |

Register now for immediate access of HFS' research, data and forward looking trends.

Get Started